Another Chance to Scoop

by Anthony Kaauamo

Precursor to a Modern Pog Duel

LĀNA‘I COMMUNITY POOL, MAY 20, 6:47 P.M.

Dawn had just broken as I was running around the swimming pool park, a time I usually avoid because it’s when the toads freely roam in the cool darkness. I either trample over them or they hop onto my shoes.

On my first loop, I passed a mass of kids squatting and sitting around the playground pavilion. They were grouped in 3-5 around the concrete area, their cellphone flashlights illuminating the center of the circles they formed. I slowed my pace as I passed them. They were all playing pogs ‚— random. It felt like 1994 again. If those kids had worn flojos instead of crocs, I might have believed I had accidentally time-traveled.

Recognizing some of the kids from my apartment complex, I asked how they knew the game and where they got their pogs. “I won them,” Jayer Pablo, an outspoken 7th grader, told me. I mentioned that I had a booklet with over 200 pogs somewhere in my attic. “Give me some then, Uncle,” Jayer said. I shook my head, “You need to earn it.” “How?” he asked. “Only way is by beating me,” I challenged.

The Pog Resurgence Led by Kalā Manupule

The game originated in the 1920s-1930s in Hawai‘i using milk bottle caps, saw a resurgence in popularity in 1991. Named after the POG juice brand (Passionfruit, Orange, and Guava), the game spread rapidly across the United States by 1992-1993, becoming a major craze among children. By the mid-1990s, pogs had turned into a multimillion-dollar industry with commercialized caps featuring various designs.

However, schools around the nation began banning pogs around 1994-1995 due to the game’s disruptive nature, leading to arguments, theft and distractions, and it being viewed by some as a form of gambling. The popularity of pogs started to decline in 1996.

Near the ending of the 2023-2024 school year, middle school and high school kids from Lāna‘i High & Elementary School (LHES) began playing with pogs, stirring up nostalgia for those who remember the craze from the 1990s. These kids were using the same pogs that many of their parents’ generation played with. Kalā Manupule, a sophomore at LHES, is credited with reigniting this trend. “One day, I just came to school with my pogs. I was bored and remembered how big it was in elementary,” Kalā said.

Kalā moved to Lāna‘i in 2022 and is related to the Kaho‘ohalahala family. His parents are Mileka Manupule and Max Alex Manupule, Sr. “I showed it to one of my friends, and soon everyone wanted to play,” he said. His friend, Mark Ramos, was the first to join him, and they played in a corner of their homeroom. “People were curious and started asking questions about what we were playing,” Kalā said.

How Lāna‘i’s Young People Are Reimagining the Game and Building Collections

Young players are breathing new life into the classic pog game with their own variations. “There are different types of games now,” said Ziggy Palik, a freshman at LHES. “We just hit and flipped in the original game,” said Linfred Olter, “But now they’re doing random.” This randomness appeals to the current generation, who agree on custom rules before playing their version of the game. “We make our own styles to make the game more interesting.”

“Flip to Keep and Find the Pog are the most popular,” Ziggy continued. In Find the Pog, the bottom pog is shown to both players before the game starts. The goal is to hit the stack and knock the top pogs aside, but as they scatter, the bottom pog might get mixed in with them. You must separate the bottom pog by at least a pog’s length from the others before flipping it over to win. “There’s a lot of strategy involved,” said Linfred.

“We make our own styles to make the game more interesting.””

Ziggy, who started with only a few pogs, now has a sizable collection. “We got our pogs from friends, or we buy them,” he said, explaining how many of the kids built their collections. After Kalā sparked the resurgence, students began acquiring pogs in various ways. “Kalā came with 300 pogs to school,” said Brody Salik, an LHES sophomore. “At first, it was just high schoolers who started playing, and then the middle schoolers saw it and joined in.” Linfred added, “The high schoolers started playing outside of school, and then all the kids would always be around them.” This initial wave of interest quickly spread, and soon, more and more students began acquiring pogs. “Some kids bought them from others, some won them in games, and others even bought them online. They also got them from grandparents who had these Hawaiian collectible pogs, the ones with the staples on them,” said Brody, “but it started off by Kalā giving them to us.”

Some students, like Gabe Sanches, the son of Keo and Anela Sanches, who is in fourth grade, got their pogs through family connections. Gabe learned about pogs through his Aunty Alice Granito, who once won a competition and collected 600 pogs. “At school, everyone just started playing pogs,” Gabe said, “Then one day, I brought some and started playing from that.” Gabe acquired his first set of pogs at the Pineapple Festival. “There was a booth selling pogs, and I bought a lot,” he said.

Since then, he has accumulated a collection of around 1,700 pogs. When it comes to playing, Gabe explained the essentials: “You need a slider, a hitter, and you have to learn how to side hit, back hit and normal hit.” He further detailed the importance of the slider, which is a separate, more flexible pog used for specific types of hits.

“The slider is really bendy. When you hit it right, you can flip the pog over,” he said.

“Over here, around 5 o’clock, it’s going to be filled up with kids playing,” said Brody, describing the scene at the community pool. “When they run out of pogs, they drop a dollar for five and then play,” said Jojo Jackson, explaining that kids use money to buy more pogs from others in order to keep playing.

While the game has become increasingly popular, especially at the swimming pool playground and on the LHES campus, the school has discouraged students from playing for keeps, citing concerns over the gambling aspect and the potential for physical altercations.

Entrepreneurial Ventures in Selling Pogs

“A bunch of kids were playing pogs on the sidewalk at recess,” said Noah Glickstein, a fourth grader and son of Matt and Kerri Glickstein. Initially, he was surprised and unsure what they were playing. When asked if he had any pogs, he remembered his mother showing him a bag of her old pogs.

“I told her that everyone at school was playing with them,” Noah said, hoping his mom would let him take her pogs to school. Concerned they might get lost or damaged, Kerri limited how many he could take. Some carried the logo of her old school and held sentimental value.

With just those few pogs to start with, he began playing and quickly accumulated more, winning many from his peers. “I won like a thousand of them. Well, at least I have 2,000 now,” Noah said. However, not all were won through games; his collection grew significantly as he traded, played, and purchased more to build his inventory.

Seeing the rise in popularity of pogs as a business opportunity, Noah and his family decided to turn it into a venture. “We bought some pogs for him to sell,” Matt said. They promoted the pogs on the “Lāna‘i Buy and Sell” Facebook page to notify people they were available for purchase. Noah spent time selling them directly, setting up outside his house for four hours, as well as at the park and on the sidewalk outside the Youth Center.

“He went to the park, and someone ended up buying $100 worth over there,” Matt mentioned. Noah also sold pogs online, even mailing some to buyers on different islands. It took a couple of weeks for Noah to sell out his initial stock, making around $300 in total from these sales. After this quick sellout, Noah faced a decision: reinvest his profits or stop there. Matt explained the thought process: “We said, ‘Well, now you can use your profits to buy the next round. And it is another risk,’” Matt said, noting that while spending money might lead to making more, there’s no guarantee. Noah decided to reinvest, understanding that sometimes in business, you have to take risks. This experience taught him that “you might have to spend money to make money,” even with the uncertainty. After his initial success, Noah received a bulk set of 1,600 Hawaiian Islands pogs for his birthday, encouraging him to keep building on his early business journey.

Noah’s experience in the pog market sharpened his ability to value his merchandise. “The Fun Factory Pogs are super rare,” Noah remarked. Through diligent research, he learned how to accurately price his pogs before selling. If someone offered him a dollar for a Fun Factory Pog, he knew to reply: “Sorry, that’s not enough because I found most of them on eBay selling for $10.”

Historical Anecdotes from the 1990s: Patrick Cabico

In the mid-1990s, the sidewalk in front of the cinderblock building housing the girls’ and boys’ locker rooms at Lāna‘i High & Elementary School was a main area for playing pogs. This building, located next to the portables and alongside the Pedro dela Cruz gym, had a storage room between the lockers that issued between the lockers that issued kickballs, volleyballs and stilts. “That whole sidewalk was just filled with students playing. It was the hype of it,” said Patrick Cabico, a member of the Class of 2002, now living in San Jose, California. “Even before school, after school. That sidewalk was always packed. From the baseball field below to the art classroom above, kids were everywhere, flipping pogs,” he said.

The school had a lenient attitude toward pogs during this period. “It was during recess when we played the most. I remember all of us playing without any real restrictions,” said Patrick. Aunty Marjorie Silva, who was always around, kept an eye on the games. “She was like the security; she let us have fun, but she was always watching,” he said.

Just like today’s generation, Patrick and his peers made up their own versions of the game. “We used to create our own rules to make it more interesting,” he said. One of those variations involved playing with Ralph Ganir, a well-known player among his peers. “We would stack them using the tube and flip them. We’ll do like four or five of those,” Patrick said, referring to the cylindrical storage tubes that held the pogs. These tubes came in different lengths, which they used to create larger, more challenging stacks.

““We would make our own pogs. We would take milk cartons, cut out circles, and stack them and glue them together so it would be thick. And we would draw custom designs on the top...””

This creativity extended beyond just playing; it also influenced how they crafted their own custom pogs. “We would make our own pogs. We would take milk cartons, cut out circles, and stack them and glue them together so it would be thick. And we would draw custom designs on the top,” he mentioned.

Patrick also shared how he built his collection. “I never had money to buy them, so if I would have only three pogs, I would say, ‘Hey, let’s play for two pogs.’ And then I would win them and my pogs would just accumulate from there,” he said. Winning pogs became a way to build status among the players, and for many, like Patrick, it was the primary method of expanding their collection.

Cheating and Strategies from the Past

Playing pogs wasn’t just fun and games; it came with its share of emotional highs and lows. Intense competitions sometimes led to conflicts. “Rocky would cheat every time,” Patrick mentioned, referring to Rocky Sanches, Jr., LHES class of 2002, known for his notorious cheating tactics. “He would cheat and, like, make up his own rules, in-game.”

“I wouldn’t doubt that I would be changing rules for be one jerk,” Rocky admitted. One of his primary tactics involved altering the weight of his pogs to gain an advantage. “Cut open the pog, put like a penny, dime inside and glue them back. It looked like a regular pog, if you hide ‘em good,” he said. By adding weight to the pogs, they were more likely to flip others over, giving him a higher chance of winning. This technique was something Rocky learned from older kids like Randy G. and Ralph Ganir. “They used to do that, so we thought it was a good idea to follow too,” he added.

In addition to altering the weight of his pogs, Rocky confessed to other tactics he would employ if he was losing. Hiding in the covered areas of the locker rooms to avoid the wind blowing the pogs over — or at least using it as an excuse if someone was losing — was another tactic.

“We always used to blame the wind, ah, if they hit ‘em? ‘Brah, the wind, the wind,’” Rocky said.

Rocky’s competitive nature and willingness to bend the rules often had a noticeable impact on younger players. When asked if he ever made anyone cry during a game, Rocky quickly responded, “Probably Rowell Ganotisi.” He mentioned that Rowell, the younger brother of Jemalyn Ganotisi, also LHES class of 2002, lived across from Patrick and often played with the older boys despite being a few years younger. “Poor thing, Rowell,” Rocky said, recalling how the older kids, himself included, would sometimes take advantage of the younger ones’ inexperience, leading to moments where the thrill of winning for the older kids meant the younger ones, like Rowell, lost their pogs and their tempers.

As the competitive nature of the game intensified, so did the disputes. The fights that occasionally erupted due to the frustration of losing valuable pogs eventually caught the attention of the school administration. “I think only after, when things got a little bit violent,” Rocky said, referring to when the school may have started to discourage or even ban pogs on campus due to the conflicts that arose.

The Inevitable Pog Duel with Jayer

After talking with my fellow ‘90s kids, I felt a renewed sense of purpose. I had to prepare for a showdown with Jayer Pablo, the bold-mouthed 7th grader. While visiting my wife during her lunch break at the school, I ran into Jayer and told him, “Meet me at the swimming pool pavilion after school tomorrow.”

Determined to be ready, I went into my attic and dug through stacks of boxes filled with memories from my LHES days. Eventually, I found my old pogs booklet. Most of my memories from the early ‘90s are hazy, likely because of the regular seizures I suffered as a child, which might have given me brain damage. My elementary school teachers often sent notes home to my mother, concerned about my constant “spaced out” look. I remember nothing about playing pogs ...

I wanted to make sure I didn’t lose any pogs I thought might be collectible. I found two Fun Factory pogs and, like Noah Glickstein, decided to stash those away. I also took out all the Lāna‘i place name ones.

I practiced a bit on my own, but my throws were weak and inconsistent. No good. Everyone else my age sounded so confident in their ability to “scoop.” Ugh.

To lessen the sting of a potential loss, I wrapped my throwing hand in bandages. If I lost, or ended up looking like an amateur, I could blame it on the injury, claiming I wasn’t in my best form. Yes, I know. SAD.

LĀNA‘I COMMUNITY POOL, AUGUST 7, 2:00 P.M.

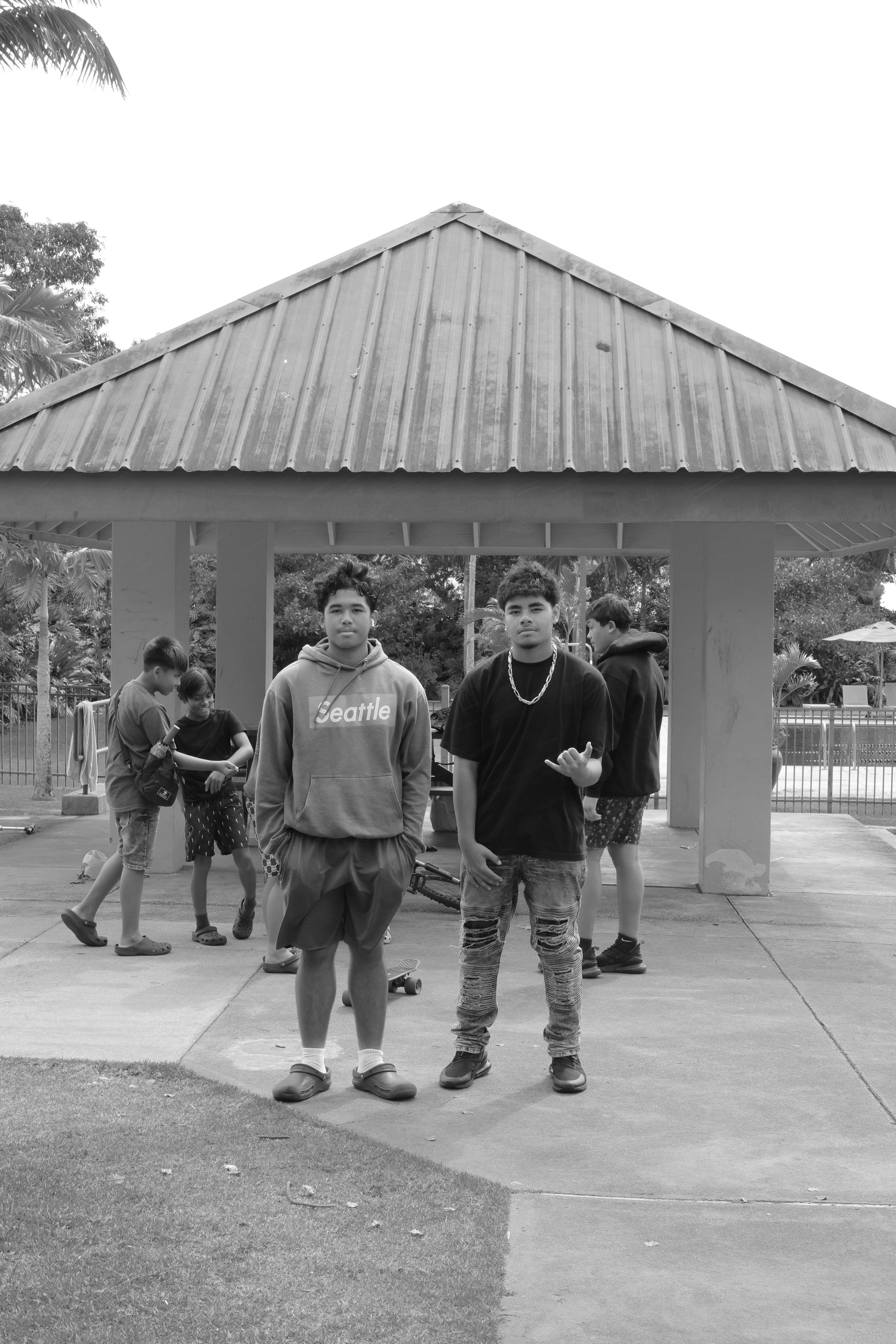

I waited by the pavilion at 2:00. My brother, Henry Sheldon Eskaran III, accompanied me. I thought his imposing presence might help throw Jayer off his “A” game and give me a winning chance.

Fifteen minutes passed. Jayer was a no-show. “Guess I win by default,” I told Sheldon. “A win is a win.” On our way back to the County parking lot, we saw a few kids playing pogs. I decided that since I was already there, I might as well try a hand. My brother had to leave, so I was left to go it alone.

One of the kids, Mistine Cornelius, accepted my challenge. She told me she was a cousin of Jayer’s. We agreed to play “Flip to Keep.” To decide who would throw first, a pog is flipped in the air. I chose heads. It landed on tails. Mistine was up for the first throw.

She hit the pogs with accuracy and strength. I was in trouble. As I clumsily made my own throw, guess who decided to finally show up … Jayer.

He greeted me by immediately making some disparaging comments about my ability, saying he told his friends that I “was the worst.” I tried to keep my focus, but it was hard with his constant taunts. “What a failure,” he muttered as I fumbled my next throw.

I tried to stall, asking Mistine about her slammer. She was using a regular pog, which was no comfort to me. “There’s wind,” I complained, trying to excuse my poor performance. “And my hand is injured.”

Mistine was unfazed and continued to play with precision. Jayer’s mocking didn’t help my confidence. “Oh, unbelievable,” he said after one particularly weak attempt of mine.

“I don’t need any commentary, okay? I’m injured,” I said, more to myself than anyone else.

After losing to Mistine, I tried to regain some dignity. “Okay, you know what? I was being nice on that one,” I said.

But Jayer wasn’t buying it. “You’re being nice? Don’t be nice to me!”

He demanded I “drop five” from my booklet as part of our bet. Reluctantly, I let him take five of my cherished pogs. “Where did you get these?” he asked, clearly impressed by my vintage collection.

“Akamai Trading … it was over 30 years ago,” I replied, remembering that pink building where strawberry and Coke Icees were sold, and the sandy playground across 8th street, filled with kids on animal spring riders, marbles rolling in circles we drew with our fingers in the dirt. Those were the days when the pineapple plantation had just closed, and everyone began working at the hotels.

Jayer stared at me blankly for a second before saying, “They’re going to be mine now.”

After winning the initial flip, Jayer hit the stack like a hammer driving a nail, flipping pogs with each strike. “You watching, Uncle?” he asked with annoying glee. Like a rusty gate in the wind, I swung at the stack, barely making contact. As the game went on, Jayer’s confidence grew, and my excuses ran thin. My hand was injured, it was windy, and the ground was too uneven — but none of these mattered. Jayer was simply better.

“The old game brought me a new challenge, and even though I didn’t come out on top, it was a reminder of the past and a lesson in humility. ”

In the end, I had to concede. “Okay, Jayer, my arm cannot handle any more ...” I said, rubbing my bandaged wrist. I watched as he celebrated his victory, feeling a mix of frustration and amusement. The old game brought me a new challenge, and even though I didn’t come out on top, it was a reminder of the past and a lesson in humility.

I let Mistine and Jayer take another 10 pogs from my booklet before heading back to my office to finish writing this article.